Obi Obi Parklands - Riparian Restoration Areas

There is a need for an extensive area of riparian forest to be established along the northern banks of Obi Obi Creek. This was recommended in the Maleny LAP and subsequent reports on the precinct land. The width of the vegetation should be sufficient to establish this as a viable wildlife habitat, taking guidance from best environmental practice. Tree selection will feature species identified in the Recovery Plans of the threatened fauna species known for this area of the precinct eg, sandpaper figs on the banks for food and protection for Mary River cod, spiny crayfish and snapping turtle. Other plant species, such as the endangered bushnut (Macadamia ternifolia), watergum (Syzygium hodgkinsoniae) and locally germinated species will be featured and identified with interpretive signs.

There is a need for an extensive area of riparian forest to be established along the northern banks of Obi Obi Creek. This was recommended in the Maleny LAP and subsequent reports on the precinct land. The width of the vegetation should be sufficient to establish this as a viable wildlife habitat, taking guidance from best environmental practice. Tree selection will feature species identified in the Recovery Plans of the threatened fauna species known for this area of the precinct eg, sandpaper figs on the banks for food and protection for Mary River cod, spiny crayfish and snapping turtle. Other plant species, such as the endangered bushnut (Macadamia ternifolia), watergum (Syzygium hodgkinsoniae) and locally germinated species will be featured and identified with interpretive signs.

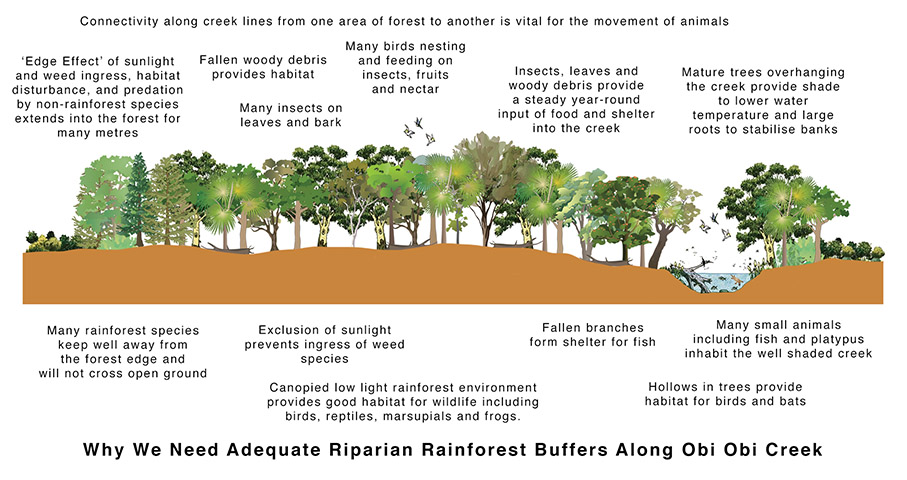

It is important that this corridor be unbroken along the creek edge with a full uninterrupted canopy cover along the entire length for the protection and movement of smaller animals. It is important that the creek be afforded shade and a good root system for habitat and bank stabilization. Below are some detailed notes explaining more fully the importance of riparian vegetation and why it is so important that we achieve an effective unbroken corridor along Obi Obi Creek from the Unitywater wetlands outflow right through to the established gallery forest remnant near Gardners Falls. This riparian corridor needs to be of sufficient width to achieve blockage of sunlight to prevent weed growth.

Click on Image to see Larger Version

The riparian vegetation will form an important link and be contiguous with the riparian vegetation occurring from the loop on Obi Obi Creek downstream towards Gardners Falls. This vegetation has been identified by Council as an Endangered Remnant Regional Ecosystem. The entire length of the riparian vegetation will be accessed via a walking path set back from the creek itself on level ground beyond the high banks. Short side trails to the creek’s edge will allow walkers to view select pools and areas of natural history interest. eg, viewing of platypus, kingfishers, herons, bush hen, butterflies, dragonflies, etc.

The trail along and through the riparian vegetation zone will form part of the main pathway linking Maleny township to Gardners Falls and in the future could form part of The Great Southeast Walk. This Queensland Government funded initiative could link Maleny with walking trails throughout southeast Queensland.

The Importance of Riparian Land

Riparian land is important because it is often the most fertile and productive part of the landscape. It often has deeper and better quality soils than the surrounding country due to past erosion and river deposition and often retains moisture over a longer period. It generally supports a higher diversity of plants and animals than the surrounding hill slopes, due to its range of habitats and food types, proximity to water, less extreme microclimate and ability to provide refuge for native plants and animals in times of stress.

Riparian land is often the last line of defence for aquatic ecosystems against the impacts of land use elsewhere in the catchment.

For the full range of functions, including protecting stream health, habitats and water quality, and ensuring development and easy maintenance of a healthy terrestrial wildlife habitat, a minimum riparian width of 25-50m each side of the waterway is recommended.

Research both in Australia and overseas has shown that grass filter strips can be effective in filtering nutrients and sediment, but only if kept to a height of at least 10-15 centimetres, with a high density of stems and leaves at ground level. They are less effective than native vegetation at filtering nutrients, particularly nitrate. Grass provides some protection of stream banks against erosive processes. Deep rooted trees however provide more protection against slumping, through stabilising effects on soils and also because they absorb water.

There are many other functions of the riparian zone that are NOT achieved by grass strips. Native riparian vegetation provides many other advantages, including:

- stabilising banks;

- providing instream detritus and woody debris, which are vital food

sources and provide habitats for instream biota; - providing shade to the stream (thereby reducing water temperatures

and growth of nuisance plants and algae); - maintaining a healthy abundance and diversity of aquatic organisms;

- providing habitat and food sources for semi-aquatic and terrestrial native species;

- providing vital wildlife corridors to allow movement of native fauna.

Vegetation Types

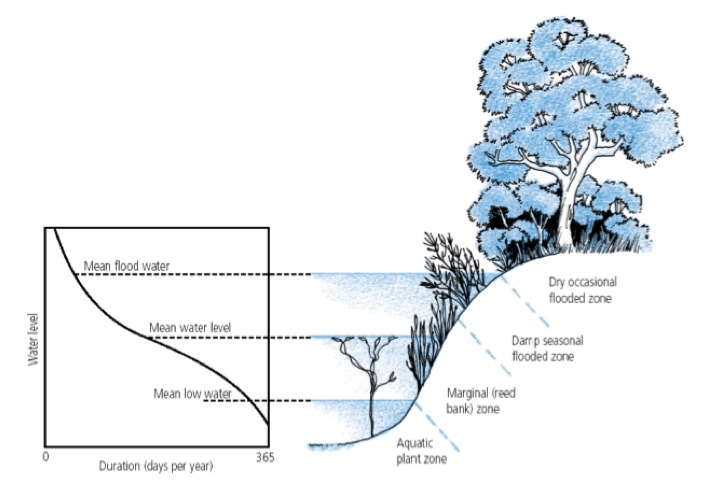

A range of vegetation types is necessary for successful stream bank stabilisation, as shown in the diagram below (from Rutherfurd et al., 1999).

Native grasses and reeds, and shrubs with flexible stems and branches, often occupy the lowest parts of the bank where they are subject to occasional inundation. They bind the soil and resist flood flows.

Further up the bank, shrubs and small trees are suitable, with an understorey of grassy species. Securely rooted species are best, preferably with a spreading, fibrous root mat that will thoroughly penetrate bank soil, and with a flexible upper portion that can bend and move in peak flows.

At the top of the streambank, large trees with a shrub understorey, or a combination of trees and grasses are ideal, as the deep rooted trees stabilise the soil.

Stable undercut banks provide shaded habitats, shelter from predators and high flows for a wide range of aquatic invertebrates and vertebrates. The fibrous root mats of some species exposed in undercut banks also offer a complex habitat for aquatic invertebrates. Many fish species seek shelter among the roots of overhanging trees (Koehn & O’Connor, 1990). Platypus construct their burrows where the roots of native vegetation consolidate the banks and prevent the burrows from collapsing. The distribution of burrows is clearly associated with the presence of intact riparian vegetation and stable earth banks (Serena et al., 2000).

Filtering Contaminants

A wide range of material enters our streams from adjacent land, including soil particles (sediment), nutrients, salt, plant material, faecal matter from stock, fertilisers, pesticides and other chemicals, hydrocarbons from vehicles, and many other contaminants from industries, urban storm water and spills.

Contaminants are carried in overland flow which can range from tiny threads of water to sheets of runoff. Dissolved nutrients can also move through the soil in underground flows entering the streams through groundwater recharge.

The sediments with their associated nutrients and other contaminants can accumulate within the stream smothering valuable interstitial habitats for aquatic life, altering the shape of the stream beds e.g. filling up deep pools which are important for some fish species and a vital refuge during dry weather, covering macrophytes making them inedible, and clogging the gills of fish and macroinvertebrates. Nutrients cause the growth of nuisance weeds and algae. Other contaminants may be toxic to aquatic life either killing them or reducing their breeding success.

Riparian vegetation, by acting as a ‘buffer’, plays an important role in moderating this transfer of contaminants and thus protecting the water quality and overall health of the waterway. Vegetation can slow the overland flow of water and catch sediment and attached nutrients and contaminants before they reach the stream channel. Water with dissolved nutrients and sediments infiltrates the soil in the filter, while sediment with attached nutrients is deposited. The plants use the nutrients, and also use up water.

Shading

Most river shade comes from riparian vegetation. The shade created by intact, healthy vegetation in small tributary streams:

- decreases the amount of direct and indirect sunlight reaching the water surface thus acting to maintain low water temperatures, and reducing daily and seasonal extremes of water temperature;

- controls primary productivity within the stream channel i.e. prevents excessive growth of nuisance plants and algae; and

- creates dim or patchy lighting thus providing habitats for predators and prey.

Research has found that cleared stream sites were on average between 3-10 degrees C warmer than forested streams and the daily fluctuations in temperature were three times greater (Bunn et al., 1999). Stream temperature can directly influence the growth and development of aquatic plants and animals. Dissolved oxygen concentrations decreases as temperature increases, further limiting plant and animal life.

Increases in water temperature also elevate rates of bacterial breakdown of organic matter and increase oxygen consumption, further reducing dissolved oxygen levels. In general, increases in light and temperature can lead to dramatic changes in the distribution and abundance of aquatic and instream productivity, and can result in an overall decline in stream health. For more details see Bunn et al., 1999.

Riparian Wildlife Habitats

Riparian lands are amongst the most productive ecosystems, supporting a greater variety and abundance of animal life than adjacent habitats (Lynch & Catterall, 1999a). They provide food, water, shelter from predators, sites for nesting and roosting, and a local microclimate with less extreme temperatures and more humid conditions than adjacent areas. Riparian areas are often corridors for wildlife movement, and provide habitat for many species. They are particularly important in areas where most native vegetation has been cleared for human use.

The high productivity of riparian lands is the result of the greater availability of water and the presence of soils which are richer in nutrients than adjacent areas. Local microhabitats are created within riparian areas, through sheltering from wind, lowering of solar radiation, increased evaporation from surface water and evapo-transpiration from plants. They are therefore often one of few parts of the landscape that can support species sensitive to desiccation.

Many native animals rely on riparian areas for all or part of their lifecycle. For example, the role of riparian forests in the conservation of butterflies has been recognised overseas (Galliano et al., 1985). The Richmond birdwing butterfly occurs mainly in riparian remnants as a consequence of clearing other habitats. Most Australian frogs are dependant on surface water for reproduction, with riparian lands providing permanent habitat for adults of some species and breeding season habitat for other species. Many Australian birds are riparian specialists e.g. azure kingfishers, while others use these habitats for specific periods or activities. Many mammals also favour riparian lands. In one eastern Australian river valley, it was found that 17 of the 20 non- flying mammals present used riparian habitats (Gregory & Pressey, 1982).

The success of riparian areas as terrestrial wildlife corridors relies highly on the width of the area. The narrower the riparian zone, the more it is impacted by edge effects, such as invasion of weed species, and effects of wind and desiccation.